Profile of intractable epilepsy in a tertiary referral center in upper Assam

Abstract

Introduction: Epilepsy is a common and diverse disorder with many different causes.Outcomes are varied with 60—70% of newly diagnosed people rapidly entering remission after starting treatment, and 20—30% developing a drug-resistant epilepsy with consequent clinical and psychosocial distress.

Methods: It is a Descriptive Cross-sectional study which was conducted in Assam Medical College and Hospital, Dibrugarh from April 2014 to April 2016. A total of 42 patients of IE attending the neurology, paediatrics and medicine department were included in the study.

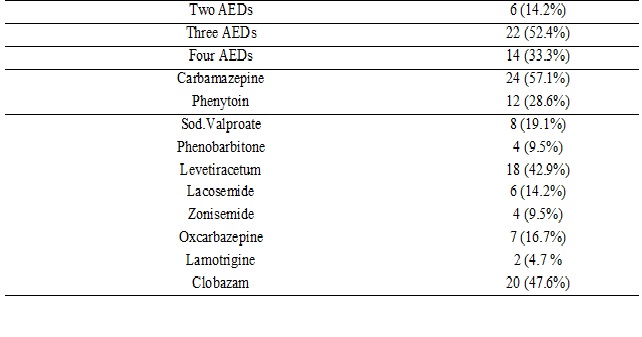

Results: Forty-two patients (males 24, females 18) with intractable epilepsy were included for the study. Maximum patients were in between 20-40 years of age (42.9%) and their mean duration of epilepsy was13.2 ± 7.13 years. The seizure frequency varied from once every month to more than 200 per (mean 26.2 ± 24.17) month. Twenty-six patients (61.9%) had partial seizures, 8 (19.1%) patients had generalized seizures and 8(19.1%) had multiple seizure semiology. Thirty-six patients had risk factors of intractable epilepsy. Seven (16.6%) patients were having family history of epilepsy and 4(9.5%) patients had history of febrile seizures. Mesial temporal lobe sclerosis (MTLS) and birth hypoxia are the two major risk factors for intractable epilepsy. EEG was abnormal in 66.7% cases, with generalized background slowing in 19.1%, focal slowing in 14.2%, generalized epileptiform discharges in 9.5% and focal epileptiform discharges in 23.8%. CT brain was abnormal in 18(42.9%) patients. MRI brains were abnormal in 25 out-off 36 patients (69.4%). Carbamazepine was the most commonly used drug (57.1%) followed by clobazam (47.6%). Phenytoin, levetiracetum, Phenobarbitone, oxcarbazepine, zonisemide, lacosemide are the other AEDs used in combination.

Conclusion: This study showed, patients with partial seizures, birth hypoxia, history of febrile seizures, family history of seizures, structural brain abnormalities and background EEG abnormalities were the most common risk factors for development of intractable epilepsy.

Downloads

References

Kim LG, Johnson TL, Marson AG, et al. Prediction of risk of seizure recurrence after a single seizure and early epilepsy: further results from the MESS trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006 Apr;5(4):317-22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70383-0.

Hauser WA, Rich SS, Lee JR, et al. Risk of recurrent seizures after two unprovoked seizures. N Engl J Med. 1998 Feb 12;338(7):429-34. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199802123380704.

Shorvon SD, Sander JWAS. Temporal patterns of remission and relapse of seizures in patients with epilepsy. In : Schmidt D and Morelli PL (eds.), Intractable epilepsy, Experimental and Clinical aspects, LERS Monograph Series, Vol., 5,Raven Press, New York, 1986; 13-24.

Shafer SQ, Hauser WA, Annegers JF, et al. EEG and other early predictors of epilepsy remission: a community study. Epilepsia. 1988 Sep-Oct;29(5):590-600.

Murray CJ, Lopez AD, editors. Global Comparative Assessment in the Health Sector; Disease Burden, Expenditures, and Intervention Packages. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994.

Hesdorffer DC, Logroscino G, Benn EK, et al. Estimating risk for developing epilepsy: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota. Neurology. 2011 Jan 4;76(1):23-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318204a36a.

Kobau R, Zahran H, Thurman DJ, et al. Epilepsy surveillance among adults--19 States, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2005. MMWR SurveillSumm. 2008 Aug 8;57(6):1-20.

Begley CE, Famulari M, Annegers JF, et al. The cost of epilepsy in the United States: an estimate from population-based clinical and survey data. Epilepsia. 2000 Mar;41(3):342-51.

Sillanpää M. Remission of seizures and predictors of intractability in long-term follow-up. Epilepsia. 1993 Sep-Oct;34(5):930-6.

Radhakrishnan K. Medically intractable partial epilepsy. Neurol India 1997; 45: 1-3.

Shafer SQ, Hauser WA, Annegers JF, et al. EEG and other early predictors of epilepsy remission: a community study. Epilepsia. 1988 Sep-Oct;29(5):590-600.

Mattson RH, Cramer JA, Collins JF. Prognosis for total control of complex partial and secondarily generalized tonic clonic seizures. Department of Veterans Affairs Epilepsy Cooperative Studies No. 118 and No. 264 Group. Neurology. 1996 Jul;47(1):68-76. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.47.1.68.

Chawla S, Aneja S, Kashyap R, et al. Etiology and clinical predictors of intractable epilepsy. Pediatr Neurol. 2002 Sep;27(3):186-91.

Eriksson KJ, Koivikko MJ. Prevalence, classification, and severity of epilepsy andepileptic syndromes in children. Epilepsia 1997;38(12):1275–1282.

Camfield C, Camfield P, Gordon K, et al. Outcome of childhood epilepsy: a population-based study with a simple predictive scoring system for those treated with medication. J Pediatr. 1993 Jun;122(6):861-8.

Huttenlocher PR, Hapke RJ. A follow-up study of intractable seizures in childhood. Ann Neurol. 1990 Nov;28(5):699-705. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410280516.

Gururaj A, Sztriha L, Hertecant J, et al. Clinical predictors of intractable childhood epilepsy. J Psychosom Res. 2006 Sep;61(3):343-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.07.018

Berg AT, Levy SR, Novotny EJ, et al. Predictors of intractable epilepsy in childhood: a case-control study. Epilepsia. 1996 Jan;37(1):24-30.

Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 3;342(5):314-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200002033420503.

Kwong KL, Sung WY, Wong SN, et al. Early predictors of medical intractability in childhood epilepsy. Pediatr Neurol. 2003 Jul;29(1):46-52.

Singhvi JP, Sawhney IM, Lal V, et al. Profile of intractable epilepsy in a tertiary referral center. Neurol India. 2000 Dec;48(4):351-6.

Camfield P, Camfield C, Gordon K, Dooley J. What types of epilepsy are preceded by febrile seizures? A population-based study of children. Dev Med Child Neurol1994;36(10):887-892

Semah F, Ryvlin P. Can we predict refractory epilepsy at the time of diagnosis? Epileptic Disord. 2005 Sep;7 Suppl 1:S10-3.

Annegers JF, Hauser WA, Elveback LR. Remission of seizures and relapse in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1979 Dec;20(6):729-37.

Berg AT, Levy SR, Novotny EJ, et al. Predictors of intractable epilepsy in childhood: a case-control study. Epilepsia. 1996 Jan;37(1):24-30.

Berg AT, Kelly MM. Defining intractability: comparisons among published definitions. Epilepsia. 2006 Feb;47(2):431-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00440.x.

Schmidt D. Two antiepileptic drugs for intractable epilepsy with complex partial seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry1982; 45: 1119-1124.

Reynolds EH, Shorvon SD. Monotherapy or polytherapy for epilepsy? Epilepsia. 1981 Feb;22(1):1-10.

Mattson RH, Cramer JA, Collins JF, et al. Comparison of carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and primidone in partial and secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures. N Engl J Med. 1985 Jul 18;313(3):145-51.doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198507183130303.

OAI - Open Archives Initiative

OAI - Open Archives Initiative