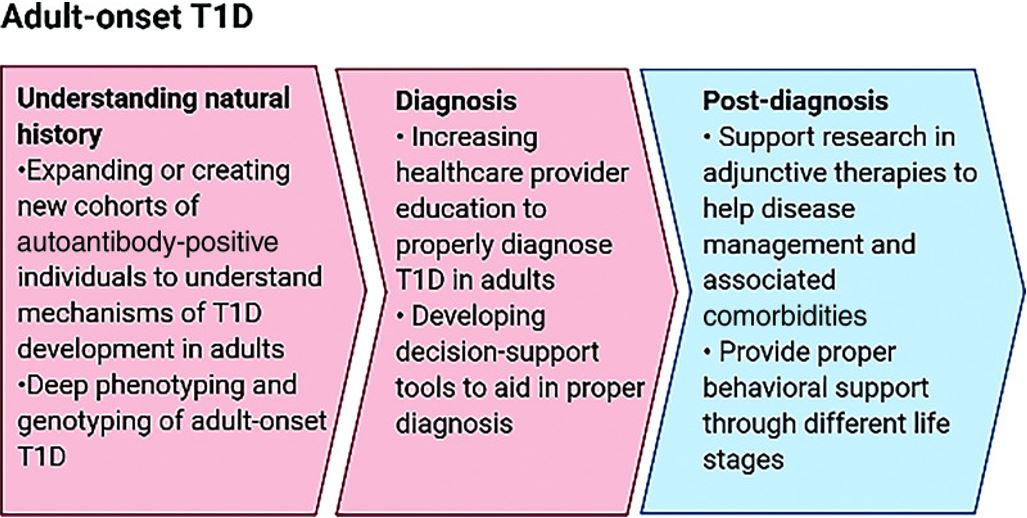

Proposed roadmap to better understand, diagnose, and take care of adults with type 1 diabetes

Adult-onset type 1 diabetes is more frequently seen than childhood-onset type 1 diabetes, as indicated by epidemiological data from both high-risk regions like Northern Europe and low-risk regions such as China.

In southeastern Sweden, the incidence of the disease among individuals aged 0–19 years is comparable to that among those 40–100 years old (37.8 per 100,000 persons per year and 34/100,000/year, respectively) [12]. Since the comparable incidence covers only two decades in children, it implies that adult-onset type 1 diabetes is more widespread. Likewise, an analysis of U.S. data from commercially insured individuals revealed a generally lower incidence in individuals aged 20–64 years (18.6/100,000/year) than in youth aged 0–19 years (34.3/100,000/year), but the total new cases in adults over 14 years amounted to 19,174 compared to 13,302 in youth [22].

Although the incidence of childhood-onset type 1 diabetes in China ranks among the lowest globally, prevalence data exhibit similar trends throughout the lifespan. From 2010–2013, the incidence was 1.93/100,000 among individuals aged 0–14 years and 1.28/100,000 among those 15–29 years old compared to 0.69/100,000 among older adults [23]. Overall, adults constituted 65. 3% of all clinically defined newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes cases in China, which aligns with estimates derived from genetically stratified data from the population-based UK Biobank utilizing a childhood-onset polygenic genetic risk score (GRS) [24].

Older individuals with type 1 diabetes represent a diverse group and have not received extensive research attention. With a long history of diabetes, experiencing hypoglycemia is frequent, independent of A1C levels.

Tailored treatment strategies involving more advanced insulin regimens and lower glycemic targets, accompanied by regular SMBG, are advised for adults. For those with compromised health and frailty, adjustments to the treatment approach are recommended.

It is essential to evaluate older adults for hypo and hyperglycemia, hypertension, physical limitations, impairments in vision, hearing, and cognition, pain, support systems, urinary incontinence, multiple medications, depression, nutritional issues, risk of falls and the requirement for social services.

The focus of the treatment plan should be on reducing the occurrence of hypoglycemia, especially severe hyperglycemia while addressing recognized physical, emotional, and social obstacles to improve safety and quality of life. In the future, new insulin preparations and technological advances are expected to contribute to better therapeutic approaches for the elderly population.

It is also essential to take into account the psychological impacts of a type 1 diabetes diagnosis in adults. Major adjustments in all facets of life are typically required, and the illness can influence both workplace and family environments. Similar to other chronic disease diagnoses, patients can be expected to go through the typical stages of grief and general practitioners have a crucial role in assisting these patients to navigate the sorrow associated with the diagnosis.

In addition to providing a precise and timely diagnosis of the illness, educating and fostering confidence in the adult newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes is vital for the individual’s capability to manage their condition independently. There is a requirement not only for guidance and assistance from the general practitioner but also for considering supplementary counselling from allied health professionals like psychologists to achieve the best possible support and patient results.

Conclusions

The six cases presented in this study indicate that type 1 diabetes can be diagnosed at any age. The age of onset of diabetes was 27,34,55,56,67 and 72 years in these adults. So diabetologists/physicians when they come across persons with classical symptoms of polyuria, polydipsia,

©

©